CALL FOR PAPERS 'War, Black Markets and Price indices, 19th and 20th centuries'

Online Seminar – Bimonthly – First Monday of the Month 12.00 PM (C.E.T.)

Maison Française d’Oxford – IDHE.S – Waseda University I Patrice Baubeau & Masato Shizume

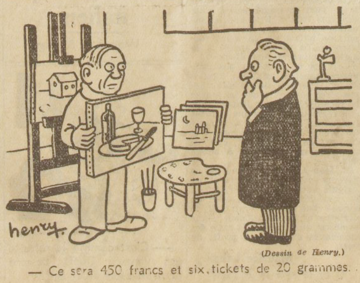

L’Œuvre, 6 January 1941 - Cartoon by Henry (Source: Retronews)

This online seminar is a follow-up to the 19 March online workshop. Its aim is to prepare for a collective volume to be published in 2028.

Rationale:

Inflation has recently made a notable comeback (Visco 2023). It had never completely disappeared, but until recently it appeared to be confined to bad public policies, such as grossly unbalanced government budgets (Argentina), misguided monetary policy (Turkey), intense civil strife (Venezuela) or near-total state collapse (Zimbabwe). Apart from such exceptional cases, the prevailing consensus seemed to have identified a “magic formula” for price stability – namely, a controlled, low but steady inflation rate, generally set at around 2 percent per annum—achieved through sound public finance and monetary policy.

The inflationary surge of 2022-2023, together with its enduring consequences has revealed the wide-ranging social and political consequences of what might be termed a pervasive “price angst”. This phenomenon has played a significant role in political turnover across many OECD countries, including France, Japan, United Kingdom, United States and even Germany. The impact of this price increase, modest by historical standards, nonetheless underscores the need for a more thorough analysis of inflation’s disruptive potential. The role of war, particularly the conflict in Ukraine, in driving inflationary dynamics must also be acknowledged.

Conflicts represent a particularly distinctive context for the study of prices. First, they typically trigger a major shift in consumption patterns, as a substantial share of national output is redirected from “civilian” to “military” uses. Second, they disrupt international flows of goods and services, curtailing exports of “strategic” resources—whether for food supply, fuelling war industries, or retaining labour to be deployed at the front—and constraining imports through blockades or shortages of foreign currency. Third, they affect social groups in highly uneven ways, across dimensions of wealth, income, urban–rural divides, ethnicity, or gender, and sometimes in seemingly paradoxical forms: as Bonnefous (1987, 34) observed, “Cold acts as a progressive tax, weighing more heavily on townhouses and large apartments.” Fourth, price information itself becomes a strategic asset in wartime, serving both as a measure of policy effectiveness and as a bargaining tool among competing authorities.

This is why “inflation”, summarized in a single series of index numbers, must be taken cum grano salis. An index, however accurate, tells only part of the story: it is an abstract figure that does not capture the lived experience of individuals (Binetti, Nuzzi, and Stantcheva 2024). Ever since price indices were first introduced at the end of the nineteenth century, this issue has persisted, raising questions about what is measured, how it is weighted, and with what implications (Ljungberg 2025). Statisticians remind us that the inflation rate is precisely that: a number designed to summarize the movement of consumer prices, weighted according to actual expenditures, thereby reflecting most strongly the experience of those who spend the most… (Easterly and Fischer 2001)

For this reason, one must exercise caution when studying “inflation” as a singular phenomenon. Inflation manifests in multiple, sometimes contradictory, ways – even simultaneously. To probe this complexity, we propose focusing on extreme situations (Rockoff 1981), in order to examine not only inflation itself, but also the related issues of measurement, price dynamics, real wages, and social policies. Wars, in particular, combine inflation – understood as rising consumer prices – with monetary disorder, fiscal imbalances, military looting and occupation, physical destruction, and shortages that can culminate in deprivation or famine.

In such contexts, what do prices actually signify? How are prices, quantities, qualities, and varieties arbitraged and determined? Is a black market truly a market, or merely a series of “discrete” transactions? How do price elasticities behave? How do staples substitute for one another? Does monetary policy retain any effectiveness? Under what conditions can rationing be efficient? What is the purpose and efficacy of price controls? Is repression the only, or even the best, strategy? How can hyperinflation – the scourge of fragile economies – be avoided? Is it even possible to construct and apply a “price index”, or should multiple indices be used? How can “real wages” and consumer “expenditures” be assessed when much, or most, of spending is either illegal or non-monetary?

From a broader perspective, how are black-market prices incorporated into official indices? And what do these indices measure: the evolution of the cost of living, overall price movements, or the purchasing power of money? The uneven quality of price indices before, during, and after war or inflationary episodes adds yet another layer of complexity.

By examining extreme situations, we aim to shed light on the nexus between prices, markets, and crises, and to understand how a price index may be suited to one context but not another – or even implicitly aligned with certain policy or political economy choices. We also seek to develop tools for more accurate assessment of price movements in times of crisis, their social impact and the ways in which they were either contained or escalated into hyperinflation. The workshop will therefore place questions and methods, not only results, at its centre.

If you are interested in participating in this online seminar and in the planned volume, please send your proposal on a war/inflation episode that raises some of the issues listed above to patrice.baubeau@gmail.com.

The seminar will host the future participants in the collective volume in order to better cross-reference the different chapters, focus the volume on common key issues and enhance the overall quality of the chapter. It will take place the first Monday of every two months (save during summer) from 12:00 to 1.20 PM CET.

The first seminar will be December 1st 2025, from Waseda University.

References

Binetti, Alberto, Francesco Nuzzi, and Stefanie Stantcheva. 2024. ‘People’s Understanding of Inflation’. Journal of Monetary Economics 103652. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2024.103652.

Bonnefous, Edouard. 1987. ‘Avant l’oubli. 2: La vie de 1940 à 1970’. Paris: Nathan.

Easterly, William, and Stanley Fischer. 2001. ‘Inflation and the Poor’. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 33(2):160–78. doi:10.2307/2673879.

Ljungberg, Jonas. 2025. ‘European Consumer Price Indices since 1870’. Cliometrica 19(1):29–80. doi:10.1007/s11698-024-00283-6.

Rockoff, Hugh. 1981. ‘Price and Wage Controls in Four Wartime Periods’. The Journal of Economic History 41(2):381–401. doi:10.1017/S002205070004362X.

Visco, Ignazio. 2023. ‘Monetary Policy and the Return of Inflation: Questions, Charts and Tentative Answers’. (122).

Additional references

Hugh Rockoff, “War and Inflation in the United States from the Revolution to the First Iraq War” (NBER Working Paper No. 21221, 2015)

Mikael Apel and Henry Ohlsson, “Monetary policy and inflation in times of war”, Riksbank, 2022.

Vincent Bignon, “Black Markets and Greys Networks for Illegal Exchanges in post WW2 Germany”, 2007

David Hackett Fischer, The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History. New York: Oxford University Press. 1996. Pp. xvi, 536.

Emile Esmaili, Michael J. Puma, Francis Ludlow, Poul Holm, Eva Jobbova, “Warfare Ignited Price Contagion Dynamics in Early Modern Europe”, arXiv:2411.18978 [econ.EM], 2024

Markus K. Brunnermeier & Sergio A. Correia & Stephan Luck & Emil Verner & Tom Zimmermann, 2023. "The Debt-Inflation Channel of the German Hyperinflation," NBER Working Papers 31298, National Bureau of Economic Research