II. The first locations: Beaumont Street, Woodstock Road and Westbury Lodge

II. The first locations: Beaumont Street, Woodstock Road and Westbury Lodge

The beginnings of the MFO, in an exhausted post-war England, were marked by resourcefulness. Until the 1950s, even though the MFO had a beautiful home on Woodstock Road to display the pomp of its garden parties, the daily restrictions imposed on staff and residents alike were hard to bear behind the scenes. But the energy of the director, Henri Fluchère, of the deputy director, Roger Hibon, and a remarkable team led by Gilberte Delahaye, Catherine Doctorow, Marie-Louise Gravagne and young Oxford graduates, made the MFO, in just a few years, a key institution in the Oxonian landscape - and beyond.

1. 28 Beaumont Street: "temporary, simple and even poor”

28 Beaumont Street (2021)

© MFO

No photograph survives of the first embodiment of the MFO at 28 Beaumont Street, a house which Henri Fluchère discovered in October 1946 as a particularly harsh winter was approaching. It is hardly surprising that no one has tried to keep its memory alive. Indeed, despite being in a pleasant location, the premises were spartan, to say the least: "The present house has a ground floor, two upper floors and a basement. It is of mediocre size and has only two habitable rooms per floor. The furniture is of the usual rental type, i.e. unstylish, motley, worn and sometimes dirty.” The rationing system still in force made it impossible to buy textiles and it was therefore necessary to do without dishcloths, towels or curtains. Fluchère therefore invited his guests and the University authorities to have lunch or dinner across the street at the Randolph. Claude Schaeffer was not impressed by Beaumont Street either, although he did manage to praise its simplicity, which was in keeping with the post-war climate of austerity: “It does not really matter if, for the moment, our “Maison” looks temporary, simple and even poor. Our Oxford friends find this quite normal in the present situation; on the contrary, too much luxury could only upset them, as they themselves know the difficulties of making ends meet.”

As soon as the idea of a French Hall of residence was mooted in 1943-44, the question of its location arose immediately and there was already talk of choosing a site “in the north of Oxford, in the Banbury road area”. When the idea of a college was abandoned, finding a house closer to the city centre became a possibility, despite the significant pressure Oxford property after the war.

In mid-1945, Claude Schaeffer mentioned the possibility of moving to a building with a garage and a garden "not far from the collegiate centre". However, Schaeffer was not sure that a large enough place could be found and suggested renting and transforming two neighbouring buildings: the first would house the library (which also served as a conference room), the dining room, the club room, the smoking room, as well as the director's apartment; the second would be devoted to student accommodation and guest rooms. These two wings of the Maison, corresponding to a separation of public and private, functional and residential spaces, will be found twenty years later in the first architectural drawings of the Maison in Norham Road.

Failing to find two buildings, Schaeffer found out in January 1946, through Alfred Ewert and Cecil Maurice Bowra, that the lease on a St John's property, the Blackhall (then held by the surgeon Henry Souttar) was about to become available. It was one of Oxford's finest mansions, nestled in the very heart of the city, in wealthy St Giles. But it had to be taken quickly because the British Council was interested. The French embassy’s cultural adviser, René Varin, was unable to secure the necessary £2,000 in time. So, the building narrowly escaped becoming the MFO, which everyone had hoped would open in a location belonging to St John's, the college most closely involved in the MFO’s history.

Despite the help of St. John’s President, Cyril Norwood, of Arthur McWatter, Secretary of the University Chest, and of the Vice-Chancellor, Richard Livingstone, nothing suitable was found to replace the Blackhall and the MFO had to be housed in 28 Beaumont Street, after considering postponing its opening for a few months. It was René Varin himself who rented, 'on his own authority', this “furnished house in a very good location but whose rather dilapidated interior would not be suitable for our business”. Fluchère could at least count on an embryonic team: Roger Hibon was recruited as assistant director and Gilberte Delahaye as executive secretary.

Although MFO had been deprived of a teaching mission, British students were to be housed there (the first class of female students dates from 1962). They were supposed to breathe a "French atmosphere" and experience "French taste". The aim was twofold: to create lasting friendships between generations of European students that would prevent further conflict, and to ensure that not only future political leaders, but also future captains of industry, would look to France as a priority when signing contracts. After the failure of the Blackhall, finding a showcase for French taste became urgent. This time it was thanks to St Hugh's that the MFO found its first home, at 72 Woodstock Road. The house, today the Principals' residence, was called 'The Shrubbery'.

2. The Shrubbery, 72 Woodstock Road: “beautiful appearance”

Staff member (unidentified, 1949)

Unknown artist - MFO Archives

Jean Cocteau and W. H. Auden on the front steps of 'The Shrubbery' (1956)

Unknown artist - MFO Archives

In December 1947 the MFO moved to 72 Woodstock Road, a house rented by St Hugh's called 'The Shrubbery', where it remained until the summer of 1963. The first photograph is one of a set of two, showing the same person working 'at the large desk' and then at their own desk, taken in the summer of 1949. It is one of the few photographs of the inside of 72 Woodstock Road and of the members of staff in the late 1940s. The second photograph was taken a few years later, on 12 June 1956. Arranged in a triptych, it shows Henri Fluchère on the left, greeting guests on the front steps with a hand in his pocket and a dog at his feet, while on the right, Jean Cocteau and W. H. Auden are talking happily. MFO staff members, as well as Monique Fluchère (daughter of Henri), between the outside and the inside of the Maison, bridge the gap between the two groups. Marie-Louise Gravagne-Fluchère, in the middle, in white, is the only one to catch the photographer's eye. This photo is not one of the better-known shots of Cocteau and Auden in their caps and gowns at the afternoon garden party, following the conferral of the honorary doctorate upon Cocteau (and to the Rector of Aix-Marseille University, Jules Blache) that morning. Taken either before or after the festivities, this more intimate photograph was not preserved as carefully as the professional ones; it was found in 2020 at the back of a wardrobe, in a sheet of white paper held together by two paper clips.

72 Woodstock Road (owned by St John's who sold it to St Hugh's in 1951) had been requisitioned as a club for the US Army and was then used to house various government departments. At the end of the war, the University of Oxford wanted to renovate it to house its Department of Statistics, but it was necessary for part of the building to be residential. The Maison Française project therefore came at just the right time. At first glance, The Shubbery seemed to be "an ideal building": "It is a beautiful house, set back from the road, with a good-sized lawn on the south and west side. It comprises a ground floor with a large entrance and three large rooms, all suitable for a library, a reading room and a reception room, [and] a first floor with seven or eight rooms of suitable size, where space could easily be found to house the three or four expected students. The kitchen, the common rooms and the outbuildings are in keeping with the house," said Henri Fluchère.

St Hugh's had offered to carry out the bulk of the refurbishment works during the summer and autumn of 1947. The entire interior would be repainted in cream, due to restrictions. It was up to the French department of Cultural Relations to find the necessary funds for the interior fittings and furniture, as the creation of a "French atmosphere" was first and foremost a matter of decoration. The Ministry therefore sent an interior designer from the 16th arrondissement, Madeleine Doré, on a mission to help Henri Fluchère prepare the most accurate quotes, based on "taste" but also on the "sturdiness" and "practicality" of the furniture – a quote that nevertheless amounted to nearly three million francs "in the first instance". The furniture, curtains, linen and crockery did not arrive from Paris until months later. Thus, some purchases still had to be made locally, like the 100 metres of "brown carpet", made by Rolls-Royce before the war but damaged during its years in storage. Fluchère bought it at a discount to cover the stairs, the first-floor corridors and three bedrooms.

The rooms were named after the regions of France: Ile-de-France, Anjou, Aquitaine, Burgundy, Brittany, Dauphiné, Franche-Comté, Languedoc, Navarre, Provence. The director's office was named Sainte-Tulle, after the village in the Basses-Alpes where Henri Fluchère was mayor. The rooms were to have a different tone with matching carpets, armchairs and curtains: green for Aquitaine, pink for Navarre, blue for Languedoc and Dauphiné, a rust colour for Sainte-Tulle… Fluchère extended this aesthetic of colour harmony to the shelves of the library, which were to contribute to the overall feeling of harmony.

For the "best French taste" to reign at the MFO, it was also necessary to banish "ultramodern and extravagant styles" - a radically different choice from the one that presided over the creation of Norham Road twenty years later. Fluchère chose desks, chests of drawers and a Louis Philippe wardrobe from the reserves of the Mobilier National, as well as Louis XV living room furniture - a sofa, four chairs, four armchairs and a fireplace screen, allegedly from the Élysée Palace, which remained at the MFO until 1995.

The 1950s were marked by the creation of "a French interior of the highest quality". The residents, who were not allowed to speak English on the premises of the Maison on pain of a fine, lived in close cooperation with the staff and the director, and this community was indeed that of a "house" or a "home". People at the MFO learnt, very early on, to be wary of ostentatious luxury, certainly out of necessity: it is the terms "charm", "discretion", "simplicity", "elegance" that are used in the archives to describe The Shrubbery. Perhaps as a sign of the desired effect, it was from Hermès that the Livre d’Or (the guest book) was ordered, in hand-sewn calfskin.

3. The inauguration: "prestige and good reputation”

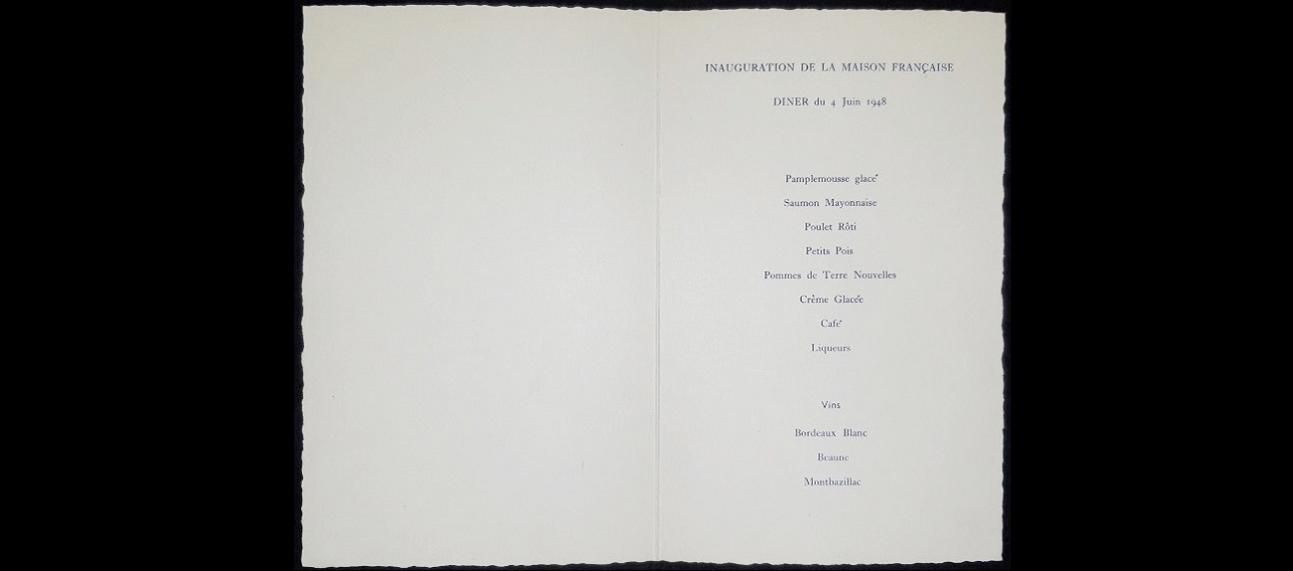

Menu, MFO inauguration dinner, 4 June 1948

© MFO - MFO Archives

The third date that marks the beginning of the MFO is 4 June 1948, the official inauguration in the gardens of The Shrubbery, in the form of a first garden party, of which the MFO still retains the tradition. Lord Simon, High Steward of the University of Oxford, cut the tricolour ribbon. The BBC made a report about the event which was broadcast in France. Surprisingly, no photo has survived in the MFO archives, but here the menu of the official dinner can be seen, while another dinner was being held at the same time, in Christ Church. Printed in French, as was fitting, the material imperfections of a still artisanal production can be seen, with the grave and acute accents added afterwards. The dishes - grapefruit, salmon and roast chicken - seem modest, but this was neither for lack of funds nor for a lack of intention to make the day a special occasion; 5% of the annual budget for 1948, i.e. nearly £260, was set aside for the inauguration day alone.

Henri Fluchère could not afford to fail on the day of the inauguration: "We shall give this ceremony our full attention, for we would like the official installation of the Maison Française in Oxford to be surrounded by all the splendour likely to give it prestige and good reputation, both by the high standard of the personalities invited and by the perfect order of the day's proceedings”. The date was chosen so that it would not compete with any event in the university calendar, which is always busy at the end of the year, but also in order to commemorate the Normandy landing. And to add to the glamour, Fluchère arranged for the Oxford University Arts Club to hold an exhibition of 19th century French painters in the drawing room, whose paintings had been loaned by private collectors from Oxford and the surrounding area. Perhaps Fluchère had anticipated (or even orchestrated?) a possible confusion in the press as to the ownership of those paintings.

But the inauguration had its absentees. The Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Lord Halifax, did not wish to attend and asked the Registrar, Douglas Veale, to save him from embarrassment. It was

Veale who suggested that Fluchère turn to Lord Simon instead. With the agreement of Ambassador René Massigli, Fluchère then invited Clement Attlee, who did not come either. On this occasion, the director took some liberty with the status of the MFO, which he did not hesitate to describe as "the latest college incorporated in the University of Oxford".

The festivities lasted all day. The morning began with speeches by Lord Simon, William Stallybrass (the Vice Chancellor who took over from Richard Livingstone in October 1947), René Massigli and Rector Jean Sarrailh. It was also a time for awards. Massigli awarded the “Légion d'Honneur” to Livingstone and Stallybrass, to Evelyn Procter, Principal of St Hugh's who had facilitated the move to Woodstock Road, to Alfred Ewert and Cecil Maurice Bowra, as well as to T. S. Eliot, whose Murder in the Cathedral had been translated by Fluchère, and Enid Starkie. Much to Claude Schaeffer's dismay, H. A. R. Gibb, the main architect of the project alongside him, was forgotten. Schaeffer criticised Henri Fluchère for this oversight and initially refused to travel to Oxford for the inauguration. The then cordial relationship between the two men deteriorated and ten years later, when Fluchère sought Schaeffer's support for the acquisition of the Norham Road site, their correspondence still bore the traces of that matter. Another key player in the MFO project, Gustave Roussy, had been dismissed following the alleged financial scandal that later drove him to suicide.

Following two concurrent lunches, one at Wadham and one at the Roebuck Inn, in the afternoon, honorary doctorates were awarded to René Massigli, Floris Delattre, Professor of British Literature and Civilisation at the Sorbonne, and Jean Sarrailh, at the Divinity School, just before the garden party. The day ended with two dinners, also occurring concurrently, one at the MFO, the other, this time, at Christ Church, and an evening reception at the MFO.

The sense of having to do much with a little, which emerges from a reading of the inauguration menu and the first activity reports, had more to do with the country's economic situation than with the lack of ambition in cultural diplomacy, including drastic import regulations, lack of raw materials, rationing and shortage of staff. It required all the energy and imagination of Henri Fluchère and his team to overcome the shortages. Wines and liqueurs, which were almost impossible to find or were sold at prohibitive prices, were sent, for example, by merchants whom Fluchère canvassed, sometimes using his Mediterranean connections: just before the garden party, he received a crate of Pastis, two crates of Cap Corse aperitif and 50 kg of Marseilles soap, free of charge.

4. Westbury Lodge: the Victorian retreat

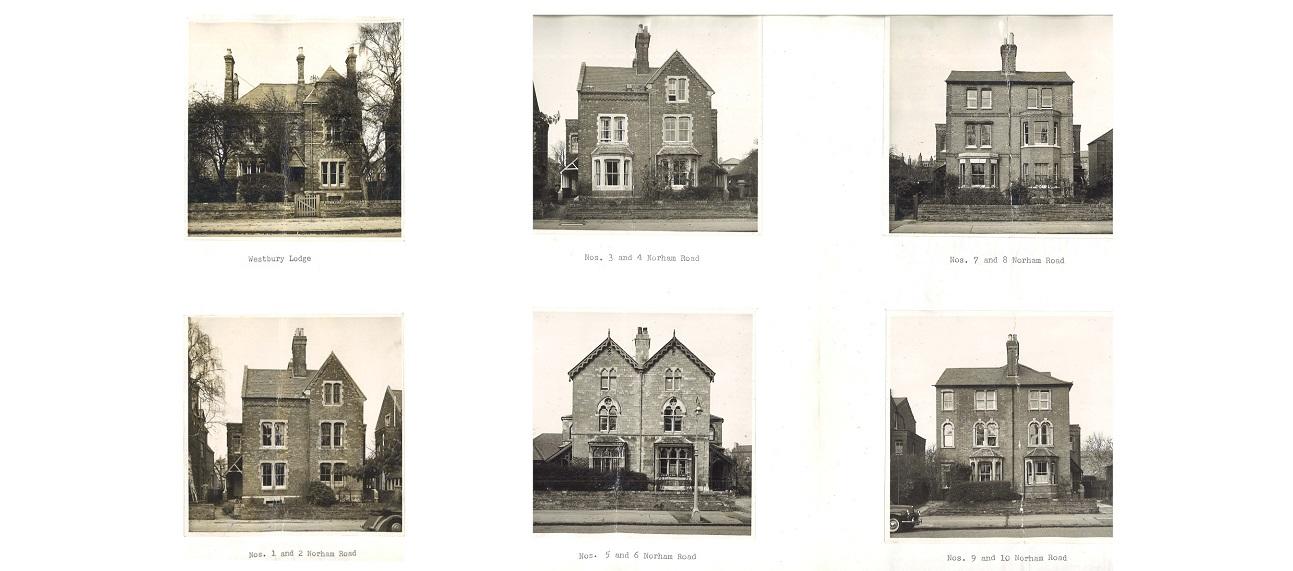

Westbury Lodge and the demolished Victorian houses, 1-10 Norham Road (undated)

© MFO - MFO Archives

By the mid-1950s, Henri Fluchère realised that he would either have to expand The Shrubbery or leave, given the pressure generated by a library that was gaining over 1000 volumes a year. In the summer of 1963, it was necessary to pack up, just as the Fluchère couple had to move back to France for good and the new director, Auguste Anglès, took up his post. While waiting for the construction of a new building, the first stone of which had been laid in 1962, all the activities of the Maison Française had to be relocated to the few rooms of a Victorian house that St John's had sold at the same time as numbers 1-10 Norham Road: Westbury Lodge. The furniture also had to be moved there, as well as the 17,500 volumes of the library. The MFO remained in Westbury Lodge for four years, from 1963 to 1967. Given the delays in the construction of the new building, and in the midst of negotiations for the UK's entry into the EEC, there were rumours in Oxford that the French government was unwilling to keep the MFO going.

With the lease on 72 Woodstock Road due to expire in September 1960, Henri Fluchère took the initiative in 1953 to negotiate the terms of its renewal. Despite the charm of the property, three disadvantages had emerged: high maintenance costs, the exponential growth of the library and the impossibility of housing more than five students, which limited both the MFO's revenue and its influence on young British minds.

At the end of 1953, the French Embassy architect, Hector Corfiato, suggested plans to extend the library and build new rooms, which were accepted by St Hugh's with amendments, but the Department of Cultural Relations eventually decided that the cost of the works could not be paid off, despite the proposal for a new 21-year lease.

At the end of 1956, St John's offered a freehold of 5,000m2 of land in Norham Road on which a “simple” house (Westbury Lodge) and five “double” houses (numbers 1 to 10) stood. Fluchère immediately saw an opportunity to make the founders' dream come true and to secure the building. The project was accepted by the Oxonian committee in May 1957, but France still had to be convinced to invest. Fluchère could count on the support of René Varin, Ambassador Jean Chauvel and Gaston Berger (Department of Higher Education). Roger Seydoux, Director of Cultural and Technical Affairs, came to the 1958 garden party and it was by telegram from the Ministry on 21 June that Fluchère found out that he could finally inform St John's of France's firm agreement. The final sale took place on 12 May 1959, following the inclusion of the MFO in the five-year cultural expansion plan and the creation of a trust – the Oxford French Trust. St John's never reversed its decision to give priority to the MFO, given the historic role the College had played in establishing the Maison, with Claude Schaeffer and H. A. R. Gibb.

The emphyteutic leases on Nos. 1 to 10 expired between 1959 and 1962, raising hopes that the MFO could fall back on one or more houses. However, all the rehabilitation projects proved too costly. St Hugh's was sympathetic and finally agreed that the MFO should remain at Woodstock Road until 30 June 1963. To compensate the college, it was decided that in 1962-63, Fluchère would accept to accommodate the very first female cohort of MFO students, fifteen years after its opening. The second cohort arrived in 1969 and 1970, after which the MFO alternated between male and female residencies.

In the summer of 1963, the MFO moved to Westbury Lodge, and the lease had to be bought back, as it would not expire until 1966. Books and furniture were crammed from the garrets to the stables; Exeter College took the piano; Nuffield College library took the periodicals. When it was time to leave, Henri Fluchère was optimistic: "It is now certain that the idea, once considered, of a reduced operation can be ruled out. The transition will thus be facilitated without the slightest damage to our prestige or our cultural action" (23 July 1963). Five months later, Auguste Anglès's first activity report mentioned, on the contrary, a cramped, dilapidated and unheated house, a wasteland whose walls were crumbling, which drew the neighbours’ and even the police’s attention, cultural activities at a standstill and a house deprived of its lifeblood: not only students but also the staff who left of their own accord in the wake of the Fluchère family or whose contracts were not renewed. Problems were also accumulating around the construction of the building. Auguste Anglès left Oxford before the end of his mandate and the MFO remained without a director for several months.