III. Norham Road

III. Norham Road

It took a long time for the Norham Road building finally to come into being, and there were many political, financial and architectural setbacks. In 1962, the year of the first female intake at the MFO, Harold Macmillan laid the foundation stone, again under the banner of European cooperation and "the age-old association between the French and British people". Five years later, André Malraux inaugurated the new building on a memorable day, proclaiming, in the new auditorium and in front of the assembled Oxford audience, that "the only force today doing battle with obscurantism is the power of the mind".

1. Major plans

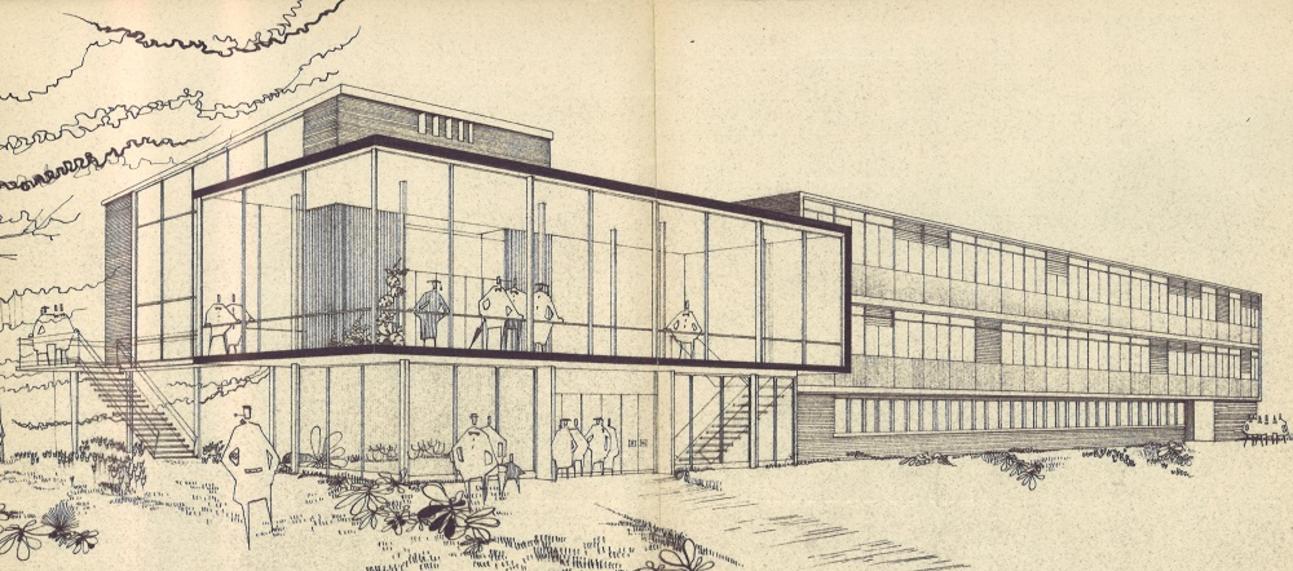

Jacques Laurent's plan for Norham Road (October 1960)

© Jacques Laurent - MFO Archives

Between 1959 and 1963, more than half a dozen projects of this type were implemented for Norham Road by Jacques Laurent, chief architect of the Bâtiments civils et Palais nationaux, who was appointed to carry out the project of building the MFO. The plans were then taken up and amended by English consultants, the architect Eduardo Dodds and his assistant, Peter French. The MFO archives hold some of Laurent’s sketches, including this ambitious plan, which was never implemented and which dates back to October 1960, after a preliminary project was abandoned in 1959. The building is shown standing lengthways, facing Norham Road. It is two storeys high and the 'functional' and 'residential' parts of the Maison are clearly distinct, separated by an elegant glass gallery.

As soon as the land belonging to St John's had been purchased, Henri Fluchère prepared a specification describing the requirements of the new building: a library of 150 to 200 m2, a periodicals room, 2 offices for the librarians, a lecture and exhibition hall (now an auditorium), a lounge, a dining room, 6 offices for administration, a kitchen, and "washbasins" on the ground floor; 10 rooms on the first floor (8 for students, 2 for guests), a common room, a bathroom, a “pantry” and a 100 m2 director's flat. On the second floor there would be “three servants' rooms and the caretaker's quarters”, and lastly, in the basement, a workshop, a laundry room, a wine cellar and a room for the archives. The garden was to include a large lawn, a garage, parking spaces, a bicycle shelter, a shed and a lodge.

Fluchère then asked Arthur Garrard, Estates Bursar of St John's, to advise him about English procedures, and it was Garrard who recommended that he find an English architect to assist Jacques Laurent. The office of Eduardo Dodds and Kenneth White was chosen.

The question remained of the architectural style to adopt. In 1957, Henri Fluchère preferred a traditional style, "a French-inspired building, whose aesthetic character, while aligning with the University's colleges, would bear witness to the good taste and elegance of our country's constructions". One of the opinions sought by Fluchère, that of Austin Gill, a fellow of Magdalen College and member of the Oxonian committee of the MFO, has survived. In a handwritten note of 25 March 1960, he too refers to “a traditional style, that is to say, one traditionally associated with the smiling elegance that the idea of good French civilisation evokes for the English. That is to say, I think - especially in Oxford - an eighteenth-century style, and if I had to be more precise, I would say a style inspired, for example, by that of the Hôtel de Noailles in Saint-Germain-en-Laye [...] It is elegant and at the same time very sober, and the proportions seem to me to be more or less exactly right.” Although traditional in style, the Hôtel de Noailles also represented "the beginning of a new style", which would allow the MFO to embody an architectural momentum towards modernity.

Without compromising on this necessary modernity, Henri Fluchère's point of view developed, and files kept in the archives testify to his growing curiosity about contemporary constructions. He sent press cuttings to Jacques Laurent about “the tower at Nuffield College”, “the new building project at Magdalen College”, the “extension” of Exeter College, “the buildings at St John's under construction”, including the student rooms “arranged like a beehive”, and left it to the architect to express himself in this vein. The MFO would “fit in” well with the Colleges, but with the latest architectural developments, rather than with their historic courtyards.

2. Architects and town planning

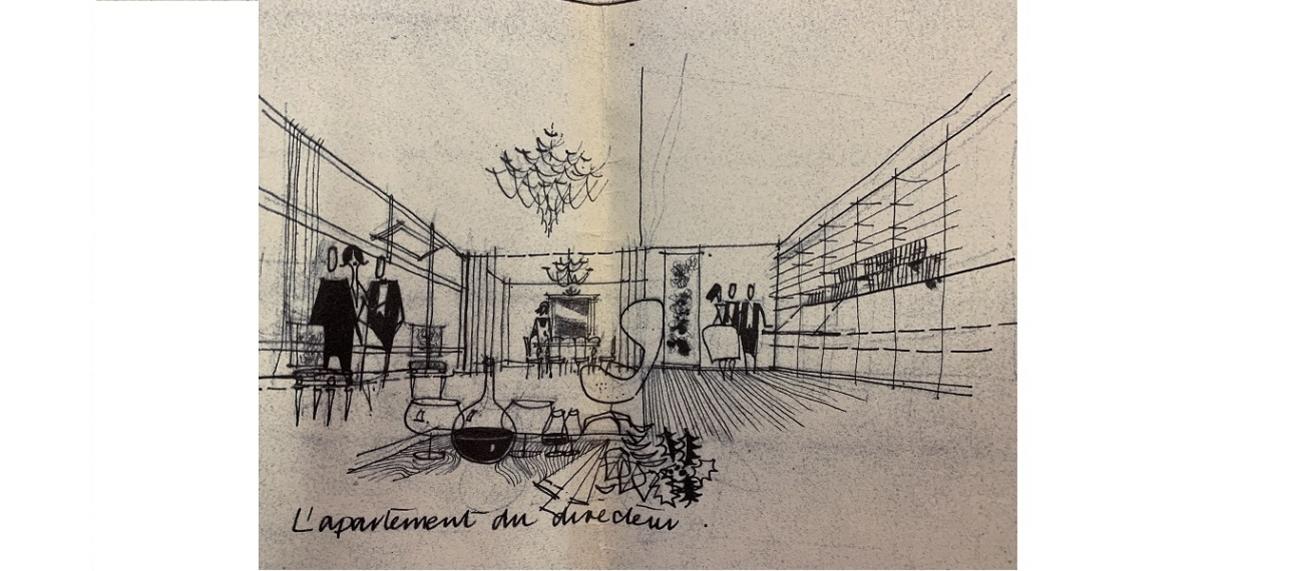

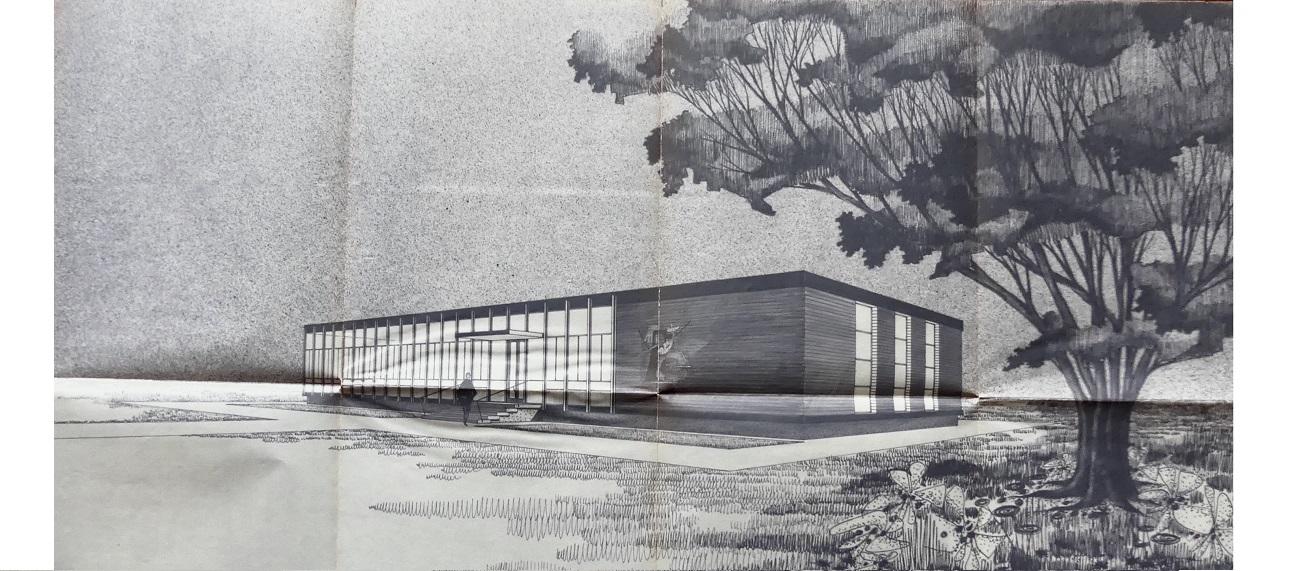

1, 2&3. Plans by Jacques Laurent, inside of the MFO (7 December 1960, details) and perspective view, February 1962

© Jacques Laurent – MFO Archive

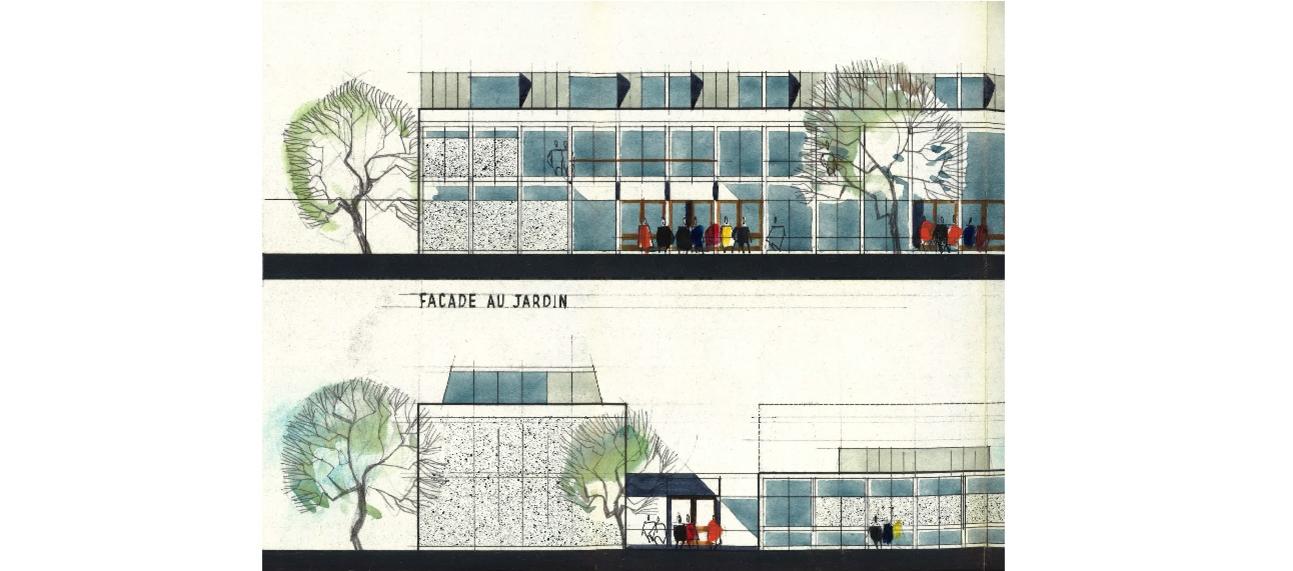

4. Plan by Eduardo Dodds, 1962

© Eduardo Dodds - MFO Archives

These are the only surviving plans in the archives of the inside of the future MFO, as imagined by Jacques Laurent in late 1960. The plate contains six drawings in total: the entrance hall, director's flat, "great hall", library, lounge and dining room. These details show the director's flat as it might have appeared at a Christmas dinner, as well as the library, for which a gallery was still planned. The second plan is a view drawn a year later, when, under budgetary pressure, the MFO lost its floors and residential part, a solution which the Oxonian town planning authorities refused to approve. The last drawing shows a phased construction plan designed by Eduardo Dodds.

For more than a year, between October 1959, when the first draft was submitted, and October 1960, nothing happened at Norham Road, despite the increasingly urgent warnings of solicitor P.E. Sandford Fawcett, who had to deal with the reluctant tenants of the Victorian houses. In October 1960, Jacques Laurent proposed three new preliminary designs, but these too were challenged. The layout, for example, did not leave enough lawn space for the receptions that the MFO had become used to with the Woodstock Road gardens. The staff rooms were on the ground floor, while the director’s flat in the middle of the students' rooms did not allow for “the quiet of a private life”. Finally, the idea of

moving the kitchens to the basement clashed with Henri Fluchère's conception of social modernity: "The basement is too reminiscent of the appalling living conditions reserved for servants in the Victorian era. It will become increasingly difficult in the future, especially in Oxford where Morris and other factories offer modernised working conditions (not to mention high wages) for domestic staff to work eight hours a day in a basement.”

On 8 June 1961, a fifth version arrived and was endorsed by Ambassador Jean Chauvel, but it was still too expensive. In October and November, two emergency meetings had to be organised in Paris. Jean Basdevant, who had taken over from Roger Seydoux at the Direction Générale des Affaires Culturelles, refused the quote and proposed, for reasons of economy, to abandon the entire residential part and one floor. The students, as well as the director, would be housed either in Westbury Lodge or in houses 3 and 4 which had not yet been demolished. The (sixth) project submitted by Jacques Laurent in February 1962 therefore no longer took into account the residential missions of the MFO, but Norham Road, located in the university area, had to accommodate students. As a result, the town planning department made it known that the project could not be accepted as it stood.

Eduardo Dodds was then called in to achieve the impossible: to maintain both the 'functional' and 'residential' missions within the agreed budget of £75,000. The first sketches were presented by Dodds's assistant, Peter French, when Dodds was already ill and had to undergo surgery. However, everything was in order to obtain planning permission in terms of layout and distribution of rooms, with the project providing for phased construction and diversification of funding sources. The Marquis de Miramon, general representative of Crédit Lyonnais in London, had been invited by the Vice-Chancellor and Henri Fluchère to discuss the possible involvement of the City. The first phase, which included the functional part of the ground floor, the library and the director's flats on the first floor, was included in the budget. The second phase included the addition of the auditorium (valued at £12,000, which Henri Fluchère suggested getting either from the University of Paris or from private sponsors). The third phase, corresponding to the second floor, included the students', guests' and staff's rooms (£25,000). As the rooms were mainly reserved for Oxonian students, Fluchère referred here to "British private initiative" to raise the necessary funds. On 24 May 1962, the planning authority gave tacit approval, knowing that Harold Macmillan was to lay the foundation stone three weeks later. In November 1962, Jean Basdevant again refused Dodds's latest quotation, for he deemed the seven offices required for staff to be excessive. And so it began again. In July 1963, when Fluchère had just gone back to France after seventeen years of Oxonian mission, he was told that Eduardo Dodds had died. The MFO would have to change not only its director but also its architect.

3. One building, three ceremonies

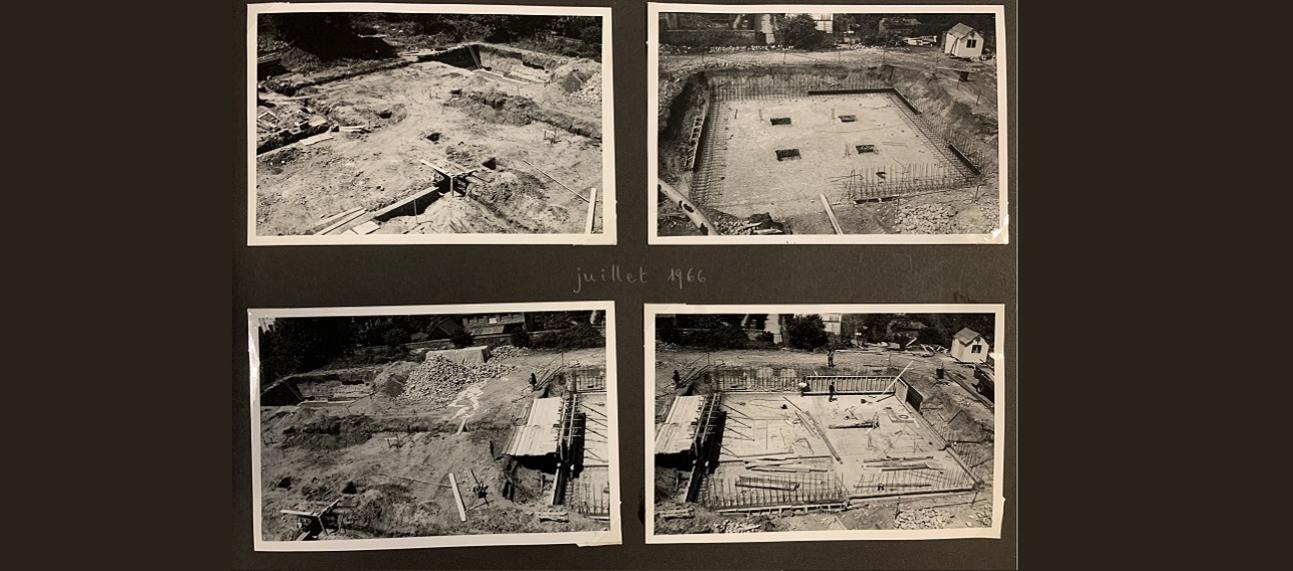

Norham Road construction site (July 1966)

© MFO - MFO Archives

Benfield and Loxley workers, topping out ceremony, Norham Road building (3 March 1967). Detail.

MFO Archives

Spectators, topping out ceremony, Norham Road building (detail, 3 March 1967)

MFO Archives

Malraux awarded an Honoris Causa Doctorate from Oxford and inauguration of the Maison Française d'Oxford (1967)

Video clip transferred by INA to the MFO in 2021 - Creator: BBC, © unknown

Following the demolition of the houses, it was not until the spring of 1966 that construction of the new building could really begin, this time under the supervision of the Ring/Howard firm whose name is engraved at the entrance of the MFO. Here, the state of the building site in July is seen. The Norham Road building was the subject of not two but three ceremonies: the laying of the foundation stone on 15 June 1962, attended by Harold Macmillan in his capacity as Prime Minister and Chancellor of the University of Oxford; the topping out ceremony on 3 March 1967 and the opening ceremony on 18 November, attended by André Malraux. The two group photographs shown here, less known than the photographs of the laying of the foundation stone or the inauguration of the building, were taken on the day of the intermediate topping out ceremony, or laying of the last stone, which traditionally honours the building workers. The first (detail) shows a group of workers from the Benfield and Loxley company that built the MFO, led by the site manager, Mr Cox. The other shows the spectators watching from the lawn as Ambassador Geoffroy de Courcel lays the final stone on the roof of the new building. Finally, the short video focuses on the ceremony in Malraux’s honor at the Sheldonian and his speech in the MFO’s auditorium. This is the only known footage showing both the interior of the building and its gardens, as Malraux inaugurated them in late 1967.

Ceremonies are part of the MFO's legacy, but behind the official photographs, reports, speeches and commemorative plaques, there are sometimes logistical and diplomatic difficulties. The closer the opening of the MFO, the more the tension rose between François Bédarida and Brian Ring, head of the architectural firm that had taken over from Eduardo Dodds. The quarrels concerned almost every subject, from the interior to the exterior. In October 1967, the library tables were unusable, the shelves were too short, the "unbearable noise" of the heating gave the impression of being "in a factory" and one month before the opening, cracks were already appearing in the walls. The architectural firm, which did not survive for very long, was no longer responding. Already embarrassed when Ring intervened during the topping out ceremony, Bédarida threatened publicly to denounce him in front of the officials on the day of the opening. Although a disaster was avoided on that day, two years of expert reports were required to establish the architect's liability and François Bédarida left his post before the work on the roof, which had become "legendary" in Oxford, could be completed.

In the early 1960s, delays in construction were also attributed to the tensions surrounding the UK's first application to the EEC. The Foreign Office did not plan to attend the laying of the foundation stone. A handwritten note states that "the Department, which did not want to send anyone, was forced to do something since the stone was to be laid by the Prime Minister of Great Britain". The reasons for this refusal are not clear, but the Director of Affaires culturelles, Jean Basdevant, did not attend and it was the Deputy Director, François Charles-Roux, who was scheduled to represent the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Macmillan and the new ambassador, Geoffroy de Courcel, emphatically praised the virtues of European cooperation. In this context, the task assigned to Vice-Chancellor A.L.P. Norrington was a little difficult: he chose to speak briefly in English, in a deliberately facetious tone, suggesting that two statues be erected at the entrance to the MFO, one of Henri Fluchère, symbolising energy; the other of Marie-Louise Fluchère, symbolising beauty.

In 1967, André Malraux dominated the festivities. The inauguration took place in the afternoon when he has just been awarded a Doctor of Civil Law (Honoris Causa), reserved for political figures, rather than a Doctor of Letters, which was usually awarded to foreign artists or writers such as Cocteau, Gide, Mauriac and others. Behind the scenes of a perfectly executed protocol in front of the press between the Sheldonian and Norham Road, as shown in the video above, mini-dramas were played out. The new MFO wall had been covered with graffiti the day before - 'Malraux yes De Gaulle no'. Colin Hardie, the public orator in charge of delivering Malraux's eulogy, found him 'tired and unprepared' (though 'better on the day'). Rector Roche finally refused to speak, believing that the place given to Malraux, alongside the University of Oxford, relegated the University of Paris to a subordinate role. François Bédarida tactfully managed to convince him in extremis that “for Oxonians, the University of Paris remained the main point of reference”. The inauguration was nevertheless engraved in the memory of the MFO – and literally, in the form of a quotation from Malraux. The highly publicised presence of Malraux, as Minister of Cultural Affairs, had a forceful impact, both culturally and scientifically, as well as diplomatically and politically. It is still one of the first images of the MFO that lingers in people’s minds.