V. Living culture

V. Living culture

Since "all the productions of the French spirit" were of interest to Oxford, the role of the MFO was "unlimited" in cultural as well as scholarly matters: theatre, concerts, cinema, exhibitions, debates, readings. The MFO also opened up to schools and the city. The library was at the heart of this. In the beginning, it was expected to contain the journals of "a kiosk on the Champs Elysées or the Place de l'Opéra" and the new literary publications of a "good Parisian bookshop", before it became a library for pleasure but also for "work" and it diversified its catalogue in Human and Social Sciences.

1. The library: an 'incomparable instrument for spiritual rapprochement'

1&2. Leaflet showing the library (1956) © MFO - MFO Archives

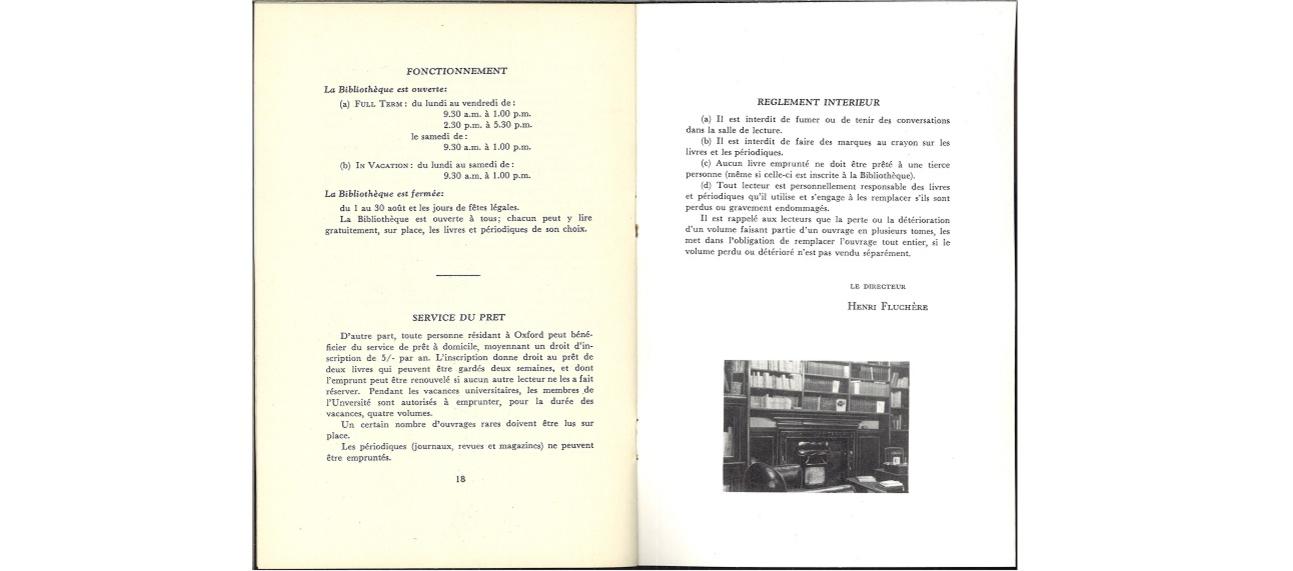

© MFO - MFO Archives

3. The record library in the original shelves (detail, 2021)

© MFO - MFO Archives

Here is the leaflet showing the library in 1956, as well as part of the original record library (classical music, variety, talking books), kept in the basement of the MFO. Henri Fluchère placed the library at the heart of the MFO's activities and made it a key part of his communication strategy. Termly newsletters (from April 1947), lists of new acquisitions, free library card for all principals, French fellows and librarians in the city, posters in each college all bear witness to determined networking. From 17 books in 1946 the library had already expanded to 17,500 in 1962. Accessible to all, whether or not they were members of the university, the books could be borrowed for a fee initially set at 5 shillings. When the library moved to Westbury Lodge in 1963, nearly 900 readers were registered and 6,000 books were borrowed each year. Thanks to its cosy atmosphere around the fireplace at Woodstock Road, its rigorous acquisition policy and its efficient catalogue, this two-sided, "work and pleasure" library became a key part of the Oxonian landscape in barely ten years.

The relocations of the MFO were largely driven by the expansion of the library, a core element of post-war cultural diplomacy. The reading room was housed in the largest room at Woodstock Road and was lined with waxed oak glass shelves, some of which still remain. There was a large central table, donated by René Varin, work tables and “around the fireplace a sofa, armchairs, low furniture, a few lamps, formed a quiet and welcoming corner”. Colour codes were experimented with: “light blue for modern novels, red for theatre, black for classical texts, dark green for modern essays, light green for criticism, garnet for poetry, etc. This rainbow had the double advantage of making it possible to distinguish at a glance the nature of the works placed on the shelves and (no less important) of adding to the decoration of the library".

The library included several collections: books, periodicals and journals, newspapers and magazines, theses from the University of Paris, as well as recordings, documentaries and some films. The works came from three sources, in addition to private donations: (1) 25 works chosen each month from the list of new arrivals (bordereau des nouveautés) published by the Ministry; (2) special orders that Fluchère was authorised to place, in addition, to complete the collection, and (3) second-hand purchases in Oxford, all of which represented about 1,000 volumes per year. From 1959 onwards, the MFO received all the new titles (45 titles) and distributed them according to their subject matter to about ten libraries in the city, and even beyond, to Durham and Newcastle.

The three-entry catalogue (authors, titles and subjects) represented the real added value of the MFO library. Each volume was accompanied by a list of corresponding articles in the journals to which the library subscribed, which were routinely searched in parallel. The system required several people to work in shifts, at least part-time, with different roles in different years ("secretary-librarian", "assistant-librarian", "secretary-typist"); the deputy director, Roger Hibon, oversaw the general policy.

The library had to carve out its own path among the collections of the Bodleian and the Taylor Institution, but also the big bookshops, such as Blackwell's. Fluchère favoured complementarity over competition, and at the outset an advisory role: "to offer Oxonians interested in French culture the same recently published volumes that they would find in a good Parisian bookshop, the same journals that they could buy from a newsstand on the Champs Elysées or the Place de l'Opéra. We can guide them in their choice of reading, inform them about current trends in French thought. We want to make the library of the Maison Française not so much a library of scholarship and reference, but an active centre for propagating French culture which will offer interested readers the ever-renewed resources of the current news.”

An academic turn was nevertheless quickly taken, in consultation with the Bodleian and Taylorian librarians whose own collections sometimes lacked sufficient copies. Contemporary literature and theatre publications continued to dominate purchases, but criticism, history, philosophy, political science and art books became increasingly important. Readers were mainly students and professors of French, PPE (Philosophy, Politics and Economics), French students applying for the licence undergraduate degree or the “agrégation” in English, and the Oxford literate public. In 1959, Fluchère left to his successors a library whose "proclaimed ambition [...] was to rise, over the years, to the level of a university library". He had designed it around literature; François Bédarida developed the humanities and social sciences, which formed nearly 25 % of the collection at the end of his mandate.

2. The university theatre

1. Mauritian students recruited by Henri Fluchère on Observatory Street (?), mid-February 1948

Unknown artist - MFO Archives

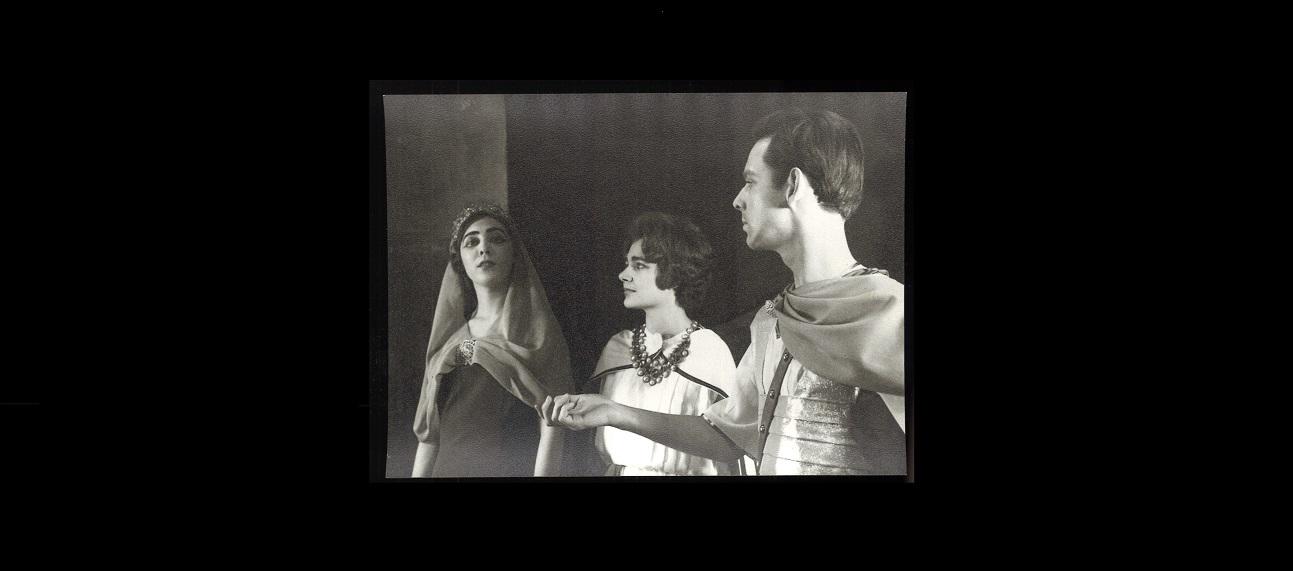

2&3. Britanicus (1962), L'École des Femmes and Andromaque (1960) at the Playhouse

MFO archives

Between 1947 and 1962, the MFO's activity reports reveal that more than 80 French plays were performed in Oxford, in the original or in translation, directed by the Oxford University French Club (OUFC), the Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS), the Experimental Theatre Club (ETC), or the Playhouse theatre group, but also by invited French companies: the Comédiens Modernes de la Sorbonne, the Théophiliens, the Le Levain Company from Poitiers and the Compagnie Henri Doublier. Among the contemporary authors, Anouilh and Giraudoux were by far the most performed, followed by Ionesco, Sartre and Roussin. Among the classics, Molière was the most popular. As Henri Fluchère's career was turned towards theatre, whether as an academic, author, translator or stage director, it was he who envisioned the MFO's contribution to live performance in Oxford. The first photograph, dated mid-February 1948, is marked “Maurice”. This alludes to the origin of the francophone Mauritian students whom Fluchère recruited to help him stage his first plays. The names are pencilled at the back of the photograph: Alfred Koenig, Philippe Kervern, Albert Ménagé, Annie and Paul Vallet, J. Paul Hein and Robert d'Unienville. The picture was taken in front of the house occupied by Hein and Menagé, possibly in Observatory Street. Koenig performed in Le Mariage forcé, then in Antigone, with Ménagé, while Paul Hein acted as business manager. The other photographs were taken a dozen years later, during performances of L'École des Femmes (1960), Andromaque (1960) and Britannicus (1962) at the Playhouse and the French Institute in London. The actors are not identified.

The MFO had two main theatrical periods, one more contemporary, the other more classical. The first was in the late 1940s, when Fluchère, having just arrived, began to establish himself as a consultant to the Oxford University French Club (OUFC): “the student clubs often come to us when they wish to perform French plays: either to be advised on the choice, to be put in touch with the author, or to obtain a translation or translator”. It is possible that Fluchère started playing a more important role following the failure of Topaze in 1948, for which the OUFC had done without his advice: “it was unwise to choose a play to be performed by amateurs, in a foreign language, in front of a foreign audience, whose charm lies solely in the satirical spirit and vivacity of its lines, and which contains almost no visual comedy. The staging, mediocre, didn’t save anything.”

Fluchère was then asked to direct plays, and he engaged the MFO staff, such as Catherine Doctorow, either to play roles or to make the costumes, sometimes from Henri Rey's models. First there was Le Mariage forcé et Tout-Homme, in 1948, an adaptation of Everyman that Fluchère had published in 1936 in Les Cahiers du Sud. He was inspired by a performance in the chapel of King's College (Cambridge), probably that of the Old Vic Theatre in 1924. This was followed by Antigone, La Paix chez soi (1949) and Jean de la Lune (1950). In 1949, the Cherwell praised Antigone as “the only really promising Oxford theatrical experiment of recent years”. After a ten-year hiatus, it was following the success of La Belle au Bois in the gardens of The Shrubbery in 1959 that Fluchère resumed theatrical activity, this time with a more classical focus: L'École des Femmes (1960), with sets by Georges Wakhévitch, Andromaque (1960), and Britannicus (1962).

Contributions to the OUFC's theatrical activities were not limited to staging plays or to financial contributions. The OUFC organised readings every term, up to twenty per year, plays for which Fluchère provided six copies, hence the number of dramatic texts in the library. Actors, playwrights and stage directors were invited at regular intervals, from T. S. Eliot to André Roussin, from Jean-Louis Barrault to Ionesco, a tradition that continued under the mandate of François Bédarida.

As a consultant, but also somewhat of an agent, Fluchère finally extended his services to OUDS to help the company set up its French tours. In 1948, the OUDS was already in Paris, Poitiers, and Avignon, with Epicœne, or The Silent Woman, by Ben Jonson. In the spring of 1949, in Paris and Bordeaux but also in Marseille and Aix-en-Provence, with Richard II. Thanks to the Oxford/Aix-Marseille Committee he had set up, Fluchère acted as an intermediary between the company and Roger Bigonnet, founder of the Mozart Festival (now the Festival International d'Art Lyrique d'Aix-en-Provence), and made a major contribution, along with Merlin Thomas, to the French tours and exchanges of university theatre groups.

Thomas (a French tutor at New College) joined the MFO steering committee in 1963. Two of the plays he directed a few years later - Le Misanthrope in 1969 and Andromaque in 1970 - were placed under the direct patronage of the Maison. From 1967 onwards, the Norham Road auditorium, while not suitable for all types of performances, was able to begin hosting plays such as La Putain respectueuse, Les Bonnes, or La Cantatrice chauve. In theatre as elsewhere, the MFO was fully playing its role as a conveyer of academic culture between France and Oxford.

3. A cultural mediation device

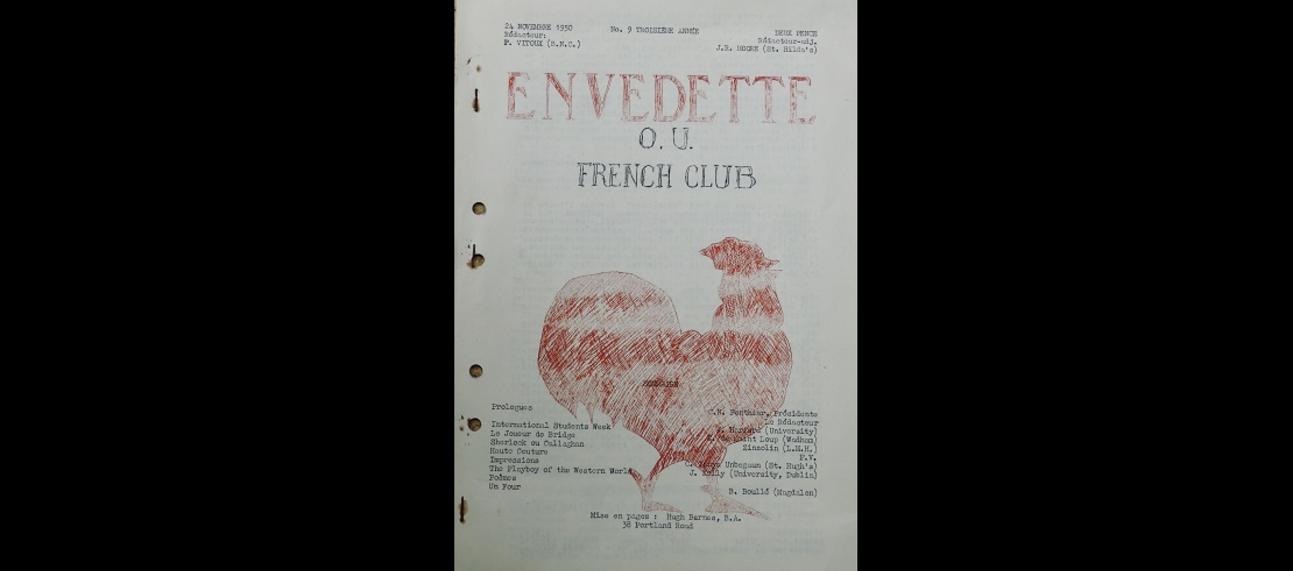

En Vedette n°9 (November 1950)

© MFO - MFO Archives

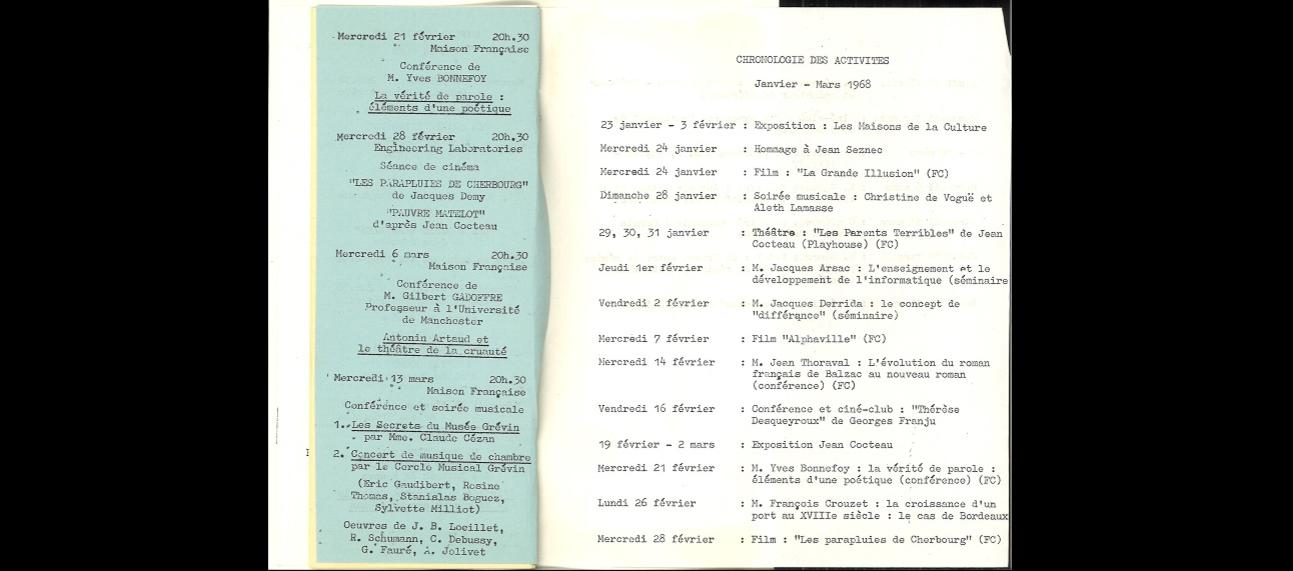

Activity programme 1967-1968 (detail)

© MFO - MFO Archives

Finally, we must mention the diversity of the MFO's cultural activities. François Bédarida's summaries speak for themselves: in four years, from January 1967 to January 1971, the MFO organised 159 activities, or contributed directly to them: conferences (47), seminars (33), film club (31 films), exhibitions (19), talks and round tables (11), concerts and recitals (11), theatrical events (7). However, even if we know the MFO today thanks to the great names that have been there, it was not, in its early days, in control of its programming. Its role was to welcome guests from the Oxford University French Club (OUFC) and from departments and colleges. Here is the cover of the 9th issue of a magazine called En Vedette, the predecessor of a short-lived La Chouette aveugle, with the OUFC logo, the red Gallic rooster. It was the OUFC's official publication, with a print run of 500 copies, "a living reflection of most of the club's activities". The magazine was mimeographed by the MFO staff. A page from the very first activity programme of the new MFO in 1967-1968 is then shown. These programmes, the forerunners of today's term cards, were introduced by François Bédarida in the late 1960s. They show the MFO's desire to free itself from the OUFC's programming. In particular, lectures by Yves Bonnefoy and Jacques Derrida are announced, as is the Jean Cocteau exhibition, the poster of which is still on display in the corridor of the MFO.

In its early years, the MFO’s only role was to welcome and hold receptions and it did not really have a cultural or academic strategy. The Director advised the Oxford University French Club (OUFC), which then decided on the programme independently: "It is the President and the Committee of the Club who take responsibility for choosing the speakers they wish to hear, from the list recommended to them either by the Director of the French Institute in London or by the Secretariat of the Alliance Française: our role is therefore limited to enlightening them on their choice, and to helping them establish a proper balance between the various subjects [...]". The MFO would prepare a dinner or reception and, depending on vacancies, would accommodate the guests on site. The OUFC and the MFO did not always agree. Henri Fluchère felt that speakers chosen by the students sometimes made “errors of judgement” at Oxford; over the years, he worked to have fewer lectures organised and to have more open topics, given the “saturation” of the Oxonian market. According to Auguste Anglès: “Organisation is poor; there are few active members, and they are very young and inexperienced”. He asked that when the new building opened, the MFO would have "a better means of action". Seminars, meanwhile, were organised either by the faculties or directly by fellows of the colleges.

Things did change in 1967. François Bédarida's room for manoeuvre increased, even though he continued to collaborate with the OUFC for the vast majority of conferences and continued to take advantage of the visits of invited personalities, for example for the Zaharoff Lecture or for the conferring of honorary doctorates (Nadia Boulanger, André Chamson...). There continued to be conferences given by Malraux, Butor, Barrault, Arrabal or Seyrig, together with interviews, debates and round tables whose format appealed to Bédarida, but the principal contrast with the previous period lay in the seminars. These were now “joint ventures of the Maison Française and a department of the University”, published in the Oxford Gazette under this double patronage. Barthes, Derrida, Lévi-Strauss, Foucault and Todorov call came to Oxford between 1967 and 1970. The transformation of a cultural centre, essentially focused on literary production, into a centre for research in humanities and social sciences was underway.

Finally, the central role of exhibitions should be mentioned, which were a cornerstone of the MFO’s activities in this period. From 1948 to 1971, 83 exhibitions were organised; some of them, inaugurated with high-profile openings, received up to 2000 visitors. Some exhibitions were lent ready-made by the Direction Générale, but others were designed and organised entirely on site. The origins of the pieces and the lenders were varied: tourist offices, galleries, museums and libraries, collectors, patrons and artists. Fluchère favoured painting, literature and books, engravings and lithographs, as well as textiles and, of course, theatre, with Provence also having pride of place (Lucien Jacques, Pierre and Suzanne Frémont, Pierre Ambrogiani, the santons of Michelle André). François Bédarida turned to the (great) history of France: La Résistance et la France Libre (465 pieces and 20 lenders, November 1968), the Droits de l’Homme (May-June 1969), Napoléon vu par les Anglais et par les Français (organised upon request from the Oxonian committee, 344 pieces and 11 lenders, November-December 1969), L’Université de Paris à travers les siècles (526 pieces, 22 lenders, February-Mars 1970), the last two created by him. He then introduced some new features, such as exhibition catalogues and school visits. At the end of this virtual tour, which retraced the first twenty-five years of the Maison Française d'Oxford, it was necessary to recall the key part of exhibitions in its cultural system.