IV. Tangible and intangible heritage

IV. Tangible and intangible heritage

The MFO also has a substantial tangible and intangible heritage. While Aristide Maillol's statue of Flore still proudly dominates the entrance to the Norham Road garden, the "coffee bean" chairs designed by Claude Lalanne, the Aubusson tapestry by Yves Millecamps and the engravings lent by the Mobilier National bear witness to France's desire to make the MFO a temple of design and craftsmanship in the late 1960s. Nothing was left to chance, from the decoration to the gardens and tableware, so that the MFO would represent the "French genius" celebrated by François Bédarida, the first director of the "new" Maison.

1. Flore, Venus, the Nymph

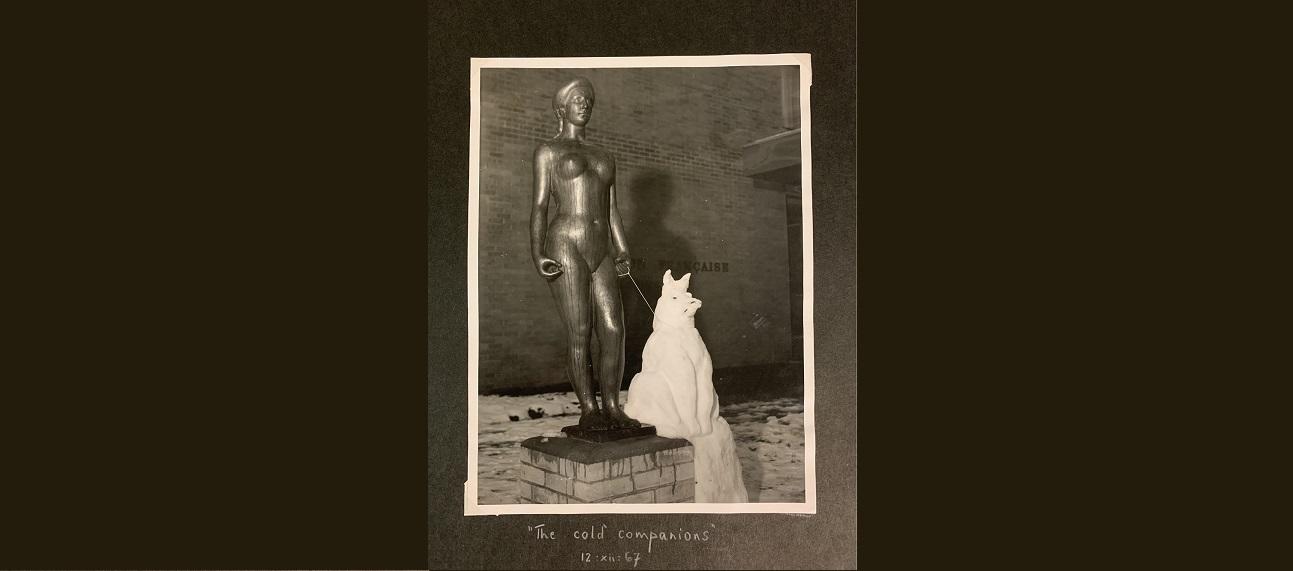

Flore with a dog, 12 December 1967

Douglas Jamieson & Co - MFO Archives

If there is one item that symbolises the MFO's heritage it is Aristide Maillol's statue of Flore, numbered 2/6. On its base, the "M" for Maillol appears with the foundry's mark and a note of the process, "C. Valsuani Cire Perdue" (some documents in the archives wrongly describe it as a sand casting by Rudier). This photograph is dated 12 December 1967, just one month after the opening of the Norham Road building and was published in the Oxford Mail. It shows the statue flanked by a large snow dog, made by the students. The caption under the photograph in the album, “The cold companions”, refers not only to the Oxonian winter but also to the opening scene of All's Well that Ends Well, the term 'cold companion' referring to virginity – “by being ever kept, it is ever lost: 'tis too cold a companion; away with't!”. The overt sexuality of the statue was a cause célèbre from the beginning of the MFO, at Norham Road, and long remained so.

The entrance to the Norham building deserved to be brightened up, but the first thought was to add touches of colour to the auditorium wall. Henri Fluchère had in mind a "vast enamel with bright colours", François Bédarida a "mosaic" or "ceramic". It was not until October 1967 that things became clearer, thanks to conversations between Bédarida and Bernard Anthonioz, head of the Service de la Création Artistique (Ministry of Cultural Affairs). It was decided to have a bronze statue and several sculptors were considered. Bédarida had a preference for Henri Laurens, but no copies of his "Mermaids" were available and the casting of "Océanide" would have been too expensive in the context of the 1 % artistic contribution. The names of Jean Peyrissac and Jean Chauvin were also mentioned, but any commission would necessarily take time. So, the Department offered to lend Maillol's statue, then in Amiens, for six months only, to solve the problem of the inauguration. It was Malraux himself who later interceded to make the deposit permanent.

Vénus, Flore, Flore nue, la Flore, la Nymphe, according to the correspondents, measures 1.60m and weighs 300kg. It arrived in Oxford in November 1967 by lorry and boat among seven other crates containing the last objects and furniture from the Mobilier National. On 13 February 1968 it was insured by Eagle Star for £12,000. By way of comparison, the Eurythmics tapestry by Yves Millecamps was insured for £1,700 and all the books in the library for £10,000.

It did not take long for the the statue to become caught in the political disputes of the late 1960s. On the eve of the inauguration, it was covered in black paint (according to Le Monde), at the same time the wall of the MFO was tagged and a few months later, on the night of 14-15 May 1968, the base was vandalised, although the statue itself was undamaged.

This mixture of the solidity of bronze and the supposed fragility of Flore worried many MFO directors, but perhaps none as much as Bruno Neveu (dir. 1981-1984). Initially worried that he could find no documentation confirming that Flore was on permanent loan, he also feared that a female nude would be vandalised "in a residential area with little surveillance and few people" (a description that is somewhat difficult to associate with North Oxford as it is today) not to mention the fact that a car dropping off guests at the entrance to the MFO could always slip on an icy patch and crash into Flore. He therefore suggested exchanging it for "a work of art (bronze or marble) that corresponds in character or style not only to architectural propriety (the building, of a perfectly neutral modernity, does not in fact call for any special correlation) but above all to the spirit of the Maison française d’Oxford, an institution of study and research at a renowned university with which it is associated. The choice of a French 19th century sculpture would certainly be the most appropriate. The work of historians on this period has [...] highlighted the great merits of academic art, its vitality of inspiration and its high quality of workmanship. Among the host of pieces lying dormant in the State's repositories, it would certainly be possible to single out one that was suitable and could be revived in the context of the Maison française d’Oxford, whose message it would reinforce through its symbolism: an invitation to an ardent and meditative search for Knowledge. A mythological figure - Minerva, Clio - or an allegorical one - Science, Education, the Genius of France - would be perfectly suited for such an artistic expression.” Mythological or allegorical, but no doubt chastely draped, such could have been Flore's replacement in the 1980s.

2. Furniture and decoration: ‘A living gallery of contemporary French design’

1. Claude Lalanne chairs

Artist unknown - MFO Archives

2. MFO dining room

Artist unknown - MFO Archives

3 & 4. Detail and bolduc of the 'Eurythmy' tapestry, based on a design by Yves Millecamps (Pinton Frères, Felletin)

MFO Archives

In 1967, the interior design of Norham Road was the subject of much attention, particularly the lounge and the dining room, considered to be the formal rooms. These photographs show the dining room. Since the creation, in 1964, of the Atelier de Recherche et de Création by Malraux, within the Mobilier National, it was possible to have prototypes made. These 24 chairs made of chromed steel, leather and rosewood, designed by Claude Lalanne in 1965, actually have a name - "coffee beans". According to the website of the Mobilier National and to Phillips, who sold the original set in 2009, the model was so named because it was designed for the offices of Olivier de la Baume, director of La Maison du Café. The leather seat has five "beans", the backrest has two. The chairs were specially designed for the MFO by the T.F.M. company, in black. At the back is the Eurythmie tapestry woven by the weaver Pinton Frères in Felletin (Aubusson tapestry) in 1965, based on a 1964 design by Yves Millecamps purchased by the Mobilier National. It is a composition of substantial proportions (2.20 x 4.55), is rather dark, and dates from the artist’s geometric period. The tapestry is signed at the lower left and the mark of the workshop is on the bolduc. Below, one can see the sideboard which was used to display vases and bowls, some from Sèvres. A white, spidery chandelier completed this outstanding ensemble, which was positioned so that it could be seen as soon as the door and the mobile teak walls, designed by Auguste Anglès to vary the space on the ground floor, were opened.

François Bédarida obtained a loan of 360,000FF for the interior design of the MFO and the transformation of Westbury Lodge. He dealt directly with three people: Bernard Anthonioz, head of the Service de la Création Artistique (Ministry of Cultural Affairs), Jean Coural (administrator of the Mobilier National) and one of his colleagues, Sylvie Lafitte, to whom many of the aesthetic choices of the new Maison are owed. In his own office, Bédarida kept some of the Louis XV pieces that the Mobilier National had lent to Henri Fluchère in 1947. The public areas of the Maison, in contrast, were to offer "visitors an attractive example of the most recent work of French craftsmen and decorative artists" - precisely what France was seeking to produce that year at the World's Fair in Montreal. To supervise the assembly of the most fragile pieces, the Mobilier National sent one of its restorers.

The aim was to present "a living gallery of contemporary French furniture" but also the "research being carried out today in France in the decorative arts", including textiles and tapestry. Twenty years earlier, the exhibition of Jean Lurçat's tapestries, which was opened by Odette Massigli (18 November 1948), in the presence of art historians and gallery owners such as Pierre Gimpel, had attracted more than 2,000 visitors to the cramped space in Beaumont Street.

It might be thought that that this idea would have been conceived very early in the design of the project, but this was not the case: it was originally planned that the furniture would simply be ordered from Heal's in London. Transforming the MFO into a showroom for French design was a solution that François Bédarida devised late in the day to overcome an awkward problem: the desire of Brian Ring, from the Ring/Howard architectural firm, to also take care of the interior design of the Maison. Failing that, Ring threatened that he would not oversee the completion of the work. Bédarida did not want to compromise and also considered that Ring's ideas “hardly showed any imaginative effort”. In the end, Ring was only allowed to design the auditorium and the library.

It is important to emphasise the wisdom of the choices and the attention to detail that François Bédarida, Renée Bédarida and Sylvie Lafitte brought to the decoration of the MFO. In addition to the two major pieces, Flore and Eurythmie, the 1967 inventory mentions twelve works chosen directly from the Fonds d'Art Décoratif (Decorative Arts Funds): a pitcher by Pierre Fouquet, two Picasso dishes from the Madoura workshops (which produced the painter's ceramics), a watercolour by Wogensky, lithographs by Poliakoff, Soulages and Estève, engravings by Ernst, Bissière (Louttre) and Prassinos, and a drawing by Szafran. Then there are fourteen pieces from the Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres (bowls, vases, an ashtray and a bust of Alexandre Brongniart). The textiles were chosen with the same care: the curtains of the MFO, for example, were designed and woven by Geneviève Dupeux, founder of the Atelier National d'Art Textile (national workshop of textile art).

The lounge raised a number of technical issues, as it had to fulfil several functions. One was more formal, for standing receptions and conferences; the other was more intimate, offering a place to retreat after dinners. As a result, rather light and mobile furnishings were positioned on the garden side, and seats, sofas, coffee tables and lamps were set around the window and on the kitchen side. The pillar was a constant source of concern, so it was finally decided to cover it with climbing plants and to place matching white seats on either side.

It was on Sunday 15 October 1967 that the students had their very first meal in the new dining room, still under construction, in a "family-style" way of life, as François Bédarida would say. Three days later, Michel Butor arrived to launch the 1967-1968 academic year.

3. The gardens

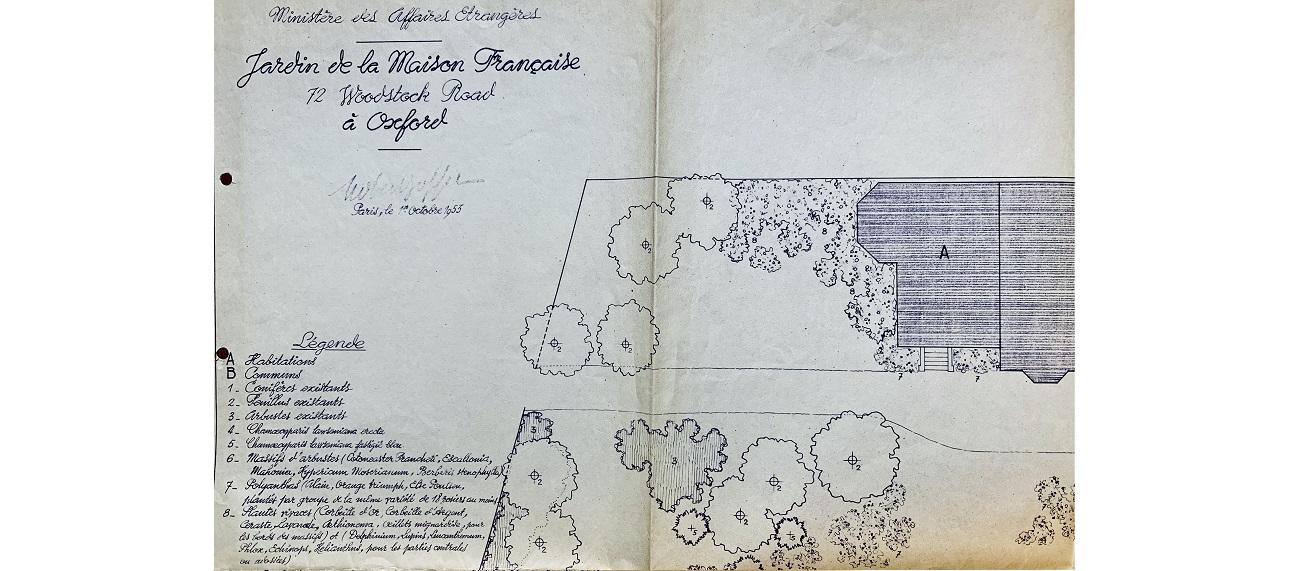

Plans and species surveys, 72 Woodstock Road, Robert Joffet, 1953

© Robert Joffet - MFO Archives

The MFO's missions required that the gardens be sufficiently extensive but they were not intended to reflect French art in the same way as the interiors. In its various forms, the Maison was French inside and English outside. It was the gardens, its direct links with the college estate in the university area (St Hugh's, St John's) and its willingness to blend into the landscape, even in Norham Road, that helped to give it a “mini-college” status in the eyes of Oxonians and guests alike. A plan detailing the garden species at 72 Woodstock Road is shown here. Dated 1 October 1953 and made for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it was in fact signed by the famous landscape designer Robert Joffet. Joffet - who was responsible for Vichy's hygiene policy in Parisian gardens, then appointed after the war to the post of chief curator of the city's gardens and parks - had come to Oxford in 1952 to study the creation of his "Shakespeare Garden" at the Pré Catelan. In addition to the gardens of the Colleges, it was therefore only natural that he should find inspiration in the Shakespearean Fluchère, who received him at the MFO, in The Shrubbery.

The 2,000m2 garden at 72 Woodstock Road was a key asset, but its day-to-day maintenance proved to be a financial drain. Although “renowned among Oxonian gardens for the variety of its species and the elegance of its floral landscape”, the garden was in a “lamentable” state after the war. Henri Fluchère was determined to restore it to its former splendour, which was “essential to the success of our annual celebration”. The garden immediately required significant investment for the time, with a lawn mower being particularly crucial. From the winter of 1949-1950, the lawn had to be tended, the trees pruned, new shrubs and rose bushes planted. Then the greenhouse, flower boxes and borders had to be redone, the paths had to be covered (several times) with gravel, and the fences had to be maintained. Robert Joffet's help was very welcome, as The Shrubbery was particularly short of flowers: "We were kindly promised help with the design of our floral landscape. I am grateful to Mr Joffet, for if he can send us next year a number of tulips, dahlias, or various perennials, it will help to beautify our garden significantly, without any expense to us.” Joffet did return to Oxford the following year, in 1953, to open an exhibition on French gardens, with “colour projections”.

When the first plans for Norham Road arrived, Henri Fluchère insisted that the layout be changed to give the garden more space. The need for an English-style garden was again emphasised, to soften the shapes of the building and “compose a pleasant landscape in the tradition of Oxford colleges”. The link between the outside and the inside would be made by the garden furniture, which was French, and by the creation of a border in the entrance hall made up of 42 pots of cacti and succulents, which attracted the attention of the ORTF (Office de radiodiffusion-télévision française) at the inauguration. This report also shows that a second tapestry had been placed just above this green space.

The garden was not created entirely from scratch: despite a 'beautiful holly tree' which was lost, there were still two chestnut trees, apple trees, pear trees, lilacs and laburnums; but François Bédarida, who considered the garden to be an “area inseparable from the rest of the Maison française”, requested, and obtained, significant funds (£1,200) to develop it. After consulting several landscape designers he decided on the Waterer company, recommended by Alan Bullock who had used them at St Catherine's College.

The objectives were clear: to better integrate the new building into Norham Road, to offer guests and students a space for relaxation but also for work, and to allow the Maison to hold garden parties, a tradition that François Bédarida intended to revive from June 1968. The archives mention four items, maintained weekly by the Charletts (father and son). They were (1) the lawn, (2) the flowerbeds (including a floral surround for Maillol’s statue of Flore, two rosebeds near the terrace and in front of the director's office), (3) a "curtain of trees, shrubs and climbing plants" to hide Westbury Lodge, and (4) a hedge (thujas, bay trees and privets) on Norham Road to secure privacy. A few years later came an unusual gift: the 6th Earl of Harrowby, a former student of Christ Church, gave the MFO cuttings “from a weeping willow planted on Napoleon's tomb in St Helena”. They were a timely supplement to Napoleon’s death mask, that the Sankey family had given to the MFO in 1967 to be exposed in a custom-made alcove near the librarian’s desk.

4. Cuisine, tableware and molecular gastronomy

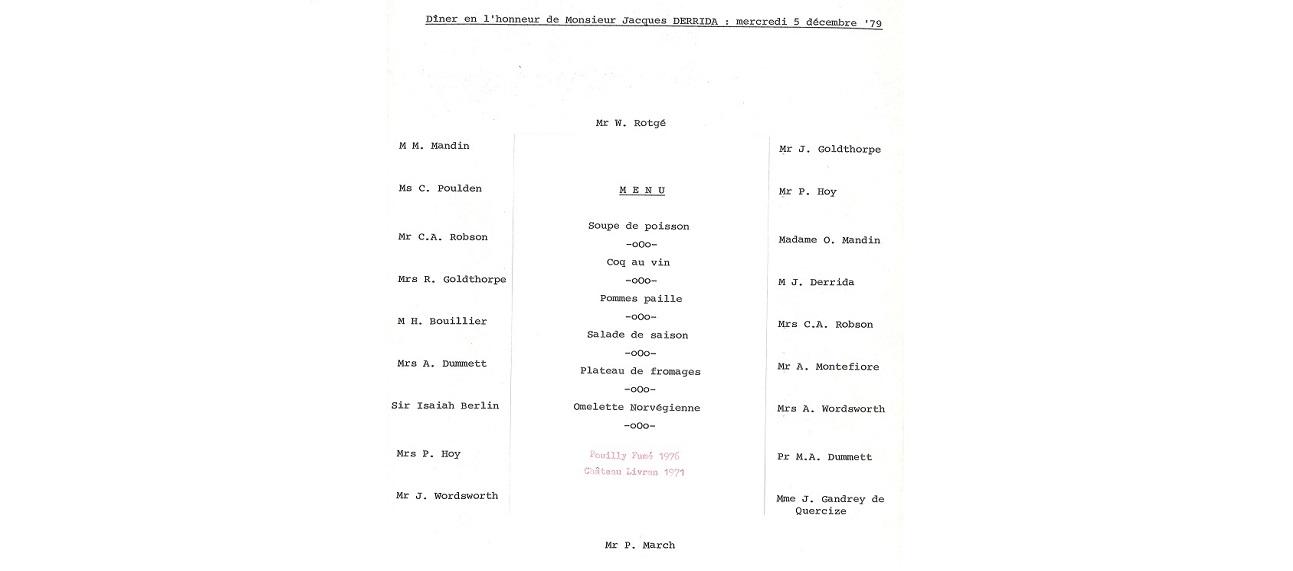

Table plan and menu, dinner in honour of Jacques Derrida, 5 December 1979 (by Christian Picaud)

© MFO - MFO Archives

The memory of the dinners organised in honour of guests survives in the MFO archives in the form of typed seating plans around the menus, preserved mainly from the reopening in Norham Road in 1967. The example presented here, dated 5 December 1979, was the occasion of Jacques Derrida's second visit to Oxford for a conference entitled “The Teaching of Philosophy”, chaired by Alan Montefiore. The speciality of the speakers determined the list of guests at the MFO; a member of staff and a French student were routinely invited. In addition to the director Henry Bouillier, the sécretaire générale Jeanne Gandrey de Quercize and Wilfrid Rotgé, a French student in residence on the MFO side, there were Ann Wordsworth and her husband Jonathan, Isaiah Berlin, Michael Dummett, together with the Professors of French Literature C. A. Robson, R. Golthorpe, P. Hoy, and their spouses. The dinner cost a reasonable amount, £89.90 for twenty people. The ingredients were ordered from the MFO’s usual suppliers at that time - Argyle, on Banbury Road, for the fish, Hedges Brothers for the meat. The house cook, Christian Picaud, kept to the tradition of French-style bourgeois cooking: fish soup (mussels, monkfish, haddock, cod and salmon), coq au vin and pommes paille, salad, cheese and omelette norvégienne.

According to Claude Schaeffer, the cellar and kitchen of the MFO were to reflect the refinement of French gastronomy and the staff were to be necessarily French, a "French chef" or a "good French cook": "it would be very useful if the Maison could fulfil the secret hope of many an Oxford fellow: to be able to discuss the affairs of our two countries over a French-style meal, served with a wine from our country chosen from the generous cellar of the Maison". Until 1948, receptions were held in various places in the city, such as White’s, where a turtle consommé was served to François Mauriac on 28 May 1947.

Without a catering licence, the MFO experienced difficult early years. Even if a caterer could be hired for receptions of more than twenty people, sugar, meat and eggs were severely rationed, stock was locked up and each food item duly counted. In the absence of a French chef, it was an English cook, Mrs Holland, who provided the meals at Woodstock Road. Henri Fluchère patriotically described her as an "excellent cook (for an English woman)"; she was one of the six people still referred to as "servants" in the activity reports.

It was only after the MFO reopened in 1967 that young, single French cooks began to be hired and housed on site. That year, the Norham Road budget also showed attention to the tableware: Gien earthenware for daily dinners, Haviland table setting, candlesticks, Christofle silverware with an elegant MF logo, Cristalleries Saint Louis, etc. The settings and dishes may have been French, but the ritual of formal dinners was Oxonian: dinner by candlelight and without a tablecloth - hence the need to find a sufficiently sturdy table, which François Bédarida wanted to be able to arrange in a horseshoe shape, in accordance with collegiate tradition. Although the kitchen in Norham Road was modest in size, the MFO offered weekday meals, receptions and formal dinners, “à la française”, albeit without ostentation. Daily menus were supervised by the sécretaire générale; formal dinners by Renée Bédarida. To give an idea of the scale of these activities, François Bédarida compiled some figures: 5868 people were invited to the MFO during his four-year tenure, of whom 1036 had lunch or dinner.

The kitchen was one of the first victims of the budget cuts of the 1980s. Among its missions, the MFO was to offer Oxford students the experience of a French-style living environment, which included three meals on the premises, in the manner of a college, and to organise various receptions (lunches and dinners, openings, cocktails, tea parties, sherry parties, garden parties...) to facilitate cultural and scientific exchanges. Depriving the MFO of its social functions therefore meant denying the very terms of the founding decree. It was in this sense that Henri Bouillier pleaded for the position of cook to be retained. He even set up a support campaign. In the MFO archives, perhaps the most remarkable of these “pleas” has survived. Dated 10 July 1981 it was made by Nicolas Kurti, a physicist and pioneer of molecular gastronomy. In perfect French, Kurti reminded the Direction générale des affaires culturelles of the importance of a cuisine that "without being luxurious" had a "typically French character": "When you attend a meal at the Maison Française, you feel carried away, for a few hours, to a corner of France in the very centre of Oxford. And it is at the Maison Française that one meets, as in the colleges, colleagues from different disciplines, but who have one important feature in common: they are francophiles and, for the most part, francophones.” This plea for the role of gastronomy in academic diplomacy did not carry the day and the MFO lost its cook.

5. Formal garden parties: an MFO concept

Garden party 1956

Artist: Wyn Griffith

On the back: [Stamp] Wyn Griffith/Jesus/Oxford. [In pencil] 1956 I

© Wyn Griffith - MFO Archives

Garden Party 1958

MFO Archives

François Bédarida in front of one of the small houses under construction on Norham Road

MFO Archives

The 1950s were the golden age of garden parties at the MFO, with up to 1800 guests attending in the gardens of The Shrubbery. These receptions were made permanent by Henri Fluchère following the success of the opening party on 4 June 1948. The garden parties reflected another quality of the first director of the MFO: his gifts as a communicator. With photographers and journalists, he transformed a modest occasion that could have remained private and academic into "the most noticed social event in Oxford", bringing together town and gown. There were artists, academics (including non-Oxonians, that Fluchère wished to thank for inviting him to give lectures), diplomats, leaders of industry, figures from the local authorities (the Mayor, the police chief, MPs) and church representatives. Among members of the French community at large, there were secondary school teachers of French and expatriates. Fluchère could count on the help of the Oxonian steering committee, ambassadors, cultural attachés and vice-chancellors who never failed to show up. The tradition was taken up again by François Bédarida in 1968, on a smaller scale (500 to 600 guests) and with a more festive character, as evidenced in particular by the small, themed wooden cabins built for the occasion.

There were fourteen garden parties at The Shrubbery between 1948 and 1962, some of which marked the history of the MFO: 1948 (opening), 1956 (tenth anniversary of the founding), 1958 (tenth anniversary of the opening when Roger Seydoux came to decide whether to buy the Norham Road site) and 1962 (laying of the foundation stone).

The garden parties took place on a Saturday in early June, a few weeks before Encaenia. They lasted two or three hours, starting in the middle of the afternoon. When French personalities were awarded an honorary doctorate during Encaenia (such as Vincent Auriol, Francis Poulenc or Fernand Braudel) there was simply a reception at the MFO. On the other hand, it was on the morning of the garden party that certain personalities received their degrees: René Massigli, Floris Delattre and Jean Sarrailh (1948), Edmond Faral (director of the Collège de France, 1952), Jean Cocteau and Jules Blache (Rector of Aix-Marseille University, 1956), Jean Chauvel (1958) and Julien Cain (director of the BnF, 1961). A second special feature, always intended to make the event solemn, was the presentation of awards to Oxford personalities by the ambassador. The number of honours given on the inauguration day was exceptional, for six were presented. The tradition continued in the 1950s, from H.A.R. Gibb (1950) to Jean Seznec (1958).

Once the dates were set and the diplomatic importance of the garden parties was assured, a balance between tradition and innovation still had to be found, year after year. For example, through the music. In 1962 - admittedly a special year - there is a list of the seven pieces played throughout the afternoon, from Handel to Darius Milhaud (without a French bias). The theatre was another source of novelty. In 1953 the OUFC (Oxford University French Club) itself announced the garden party to its members, opened by John Peters, then President of the Oxford Union, who promised an appearance by the actors of Les Mouches, which the OUFC was performing that year, “in costume”. In 1959, following the example of university theatre groups in college gardens in the summer, Fluchère combined the garden party with a performance of Jules Supervielle's La Belle au Bois under the auspices of the OUFC. The play was directed by Fluchère and performed by students, in a marquee built for the occasion, with costumes designed by Fluchère’s colleague from Rideau Gris, Henri Rey. It was quite successful and, encouraged by Jean Chauvel, Henri Jourdan later offered the troupe to play at the French Institute in London.

François Bédarida, for his part, favoured themed cabins that made the garden party look like a school fair: "three small wooden houses whose decoration changes from one year to the next. Sometimes a chalet, sometimes a country house, sometimes a guinguette or a bistro from Montmartre, these little cabins match their appearance with their sound recordings and the drinks they offer. Banners, brightly coloured parasols, white tables and blue and red canvas chairs complete the décor, complemented by the elegant variety of academic gowns”.

Fluchère and Bédarida still needed to rely on the last three ingredients of any successful garden party: the first, which was difficult to control, was the English weather in June, which forced them to consider fallback solutions, indoors or under awnings (although the expression "Fluchère weather" was coined to indicate the particularly mild weather at MFO garden parties); the second was the “refreshments”; and the third was team spirit. The type of buffets is only known for a few of the years, for example in 1951: fruit salad, sandwiches and iced coffee. Fruit, including strawberries, dominated this summer event, and for reasons of economy, the MFO had taken to sourcing its produce in the morning from the Covent Garden market, rather than from the Oxford market. Finally, the role of the garden parties in bringing groups together must be mentioned: the first directors unfailingly emphasised the commitment of the staff and students. There is little doubt that the garden parties, apart from the cameras, photographs and ambassadors, were also an opportunity to unite the teams around a common objective: to make the party more beautiful, year after year.